|

||||||

|

Notes on Forrest Bess by Andrew Masullo

|

||||||

|

The Wounded Brush by Daphne Merkin The first time I saw a painting of Forrest Bess more than two decades ago—I believe it was part of a small exhibit at a gallery on the Upper East Side and that the main event was a show of Marsden Hartley's work, but I could be misremembering—I was electrified, almost as if the daubs on the canvas had a tensile strength all their own that pulled me in. There was something about the intensity of Bess' style—the thick and uneven application of color, the almost childlike rendition of imagery, the palpable aura of anxiety—that spoke to me on a level that bypassed the usual niceties of discourse. I felt as if my subconscious were being met by Bess' subconscious, somewhere before the collective muck of socialization started up, before the super-ego began doing its work of repression and sublimation. We were meeting in a place that was kept hidden from most onlookers, one where primal conflicts about identity were allowed their say without a premature rush to judgment.

My curiosity about Bess has stayed with me since that day but although I have read up on his biography as well as some of the available criticism about his work there is something that remains elusive about him. Perhaps it has to do with his essential "outsiderness," the way he lived so entirely on his own and by his own peculiar lights despite communications with people like betty Parsons, Lincoln Kirstein and Meyer Schapiro. Although he was capable of friendship with both adults and children, Bess was in some sense the quintessential artist-as-loner, someone who looked to books and his own inner life for companionship. One might describe him as a small-town eccentric, as some critics have. Or one might think of him as he thought of himself, as that rarest of creatures, one we of secular faith tend to raise a bemused eyebrow at—a bona fide visionary, straight out of a poem by Blake or a novel by Dostoyevsky. "My painting is tomorrow's painting," Bess wrote in 1962. "Watch and see."

Forrest Bess was born in Bay City, Texas, in 1911 and already as a young boy experienced visions. He started drawing at the age of seven, mostly copying from an encyclopedia, and in 1924 took private lessons in drawing from a neighbor in Corsicana, Texas. In 1933, after attending Texas A&M college for two years and then studying architecture for a year at the University of Texas he went to work as a roughneck in the oil fields and continued to paint. He also made repeated trips to Mexico over the next six years, having fallen in love with both the land and the people. He had his first one-man exhibition in 1938 at the Witte Memorial Museum in San Antonio and was also included in a group show at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. After an extended period of military service during World War II, he suffered a mental breakdown and later made use of his hallucinations in his painting. In 1947 he returned to Bay City and set up a commercial fishing and bait camp on Chinquapin Bay on the Intracoastal Waterway, living on a strip of land accessible only by boat.

Bess remained preoccupied by his personal symbolism and what it expressed of a more universal nature his whole life, going so far as to contact C. G. Jung and to correspond with psychologists and anthropologists. He felt himself to be divided between two personalities—one more rough-and-ready and one "somewhat effeminate," as he himself described it—and eventually developed a somewhat loopy theory about the key to eternal life residing in the urethral orgasm of the pseudo-hermaphrodite. It was in support of this thesis that he kept a notebook of sketches, clippings and quotations—drawn from a wide range of sources that ranged from the Bible to Goethe—and underwent a series of surgical operations, some self-administered, in pursuit of hermaphroditic alteration. As early as 1949 he began showing at the Betty Parsons Gallery (he went on to have six solo shows with her) and during his lifetime his reputation as a painter steadily grew as did a certain interest in his ideas. He died of skin cancer at the age of 66, on November 11, 1977, in a Bay Villa nursing home.

Forrest Bess was one of those fragile, eternally misplaced, primordially nostalgic souls who occasionally come to rest on this earth. He reminds me of the consul in Malcolm Lowry's great novel, Under the Volcano, who is "homesick for being homesick." Although it is something of a commonplace to say that an artist paints out of a sense of psychic injury, I think in Bess' case he painted out of an urgent need to restore an original apprehension of harmony. "Art is a search for beauty" he wrote Betty Parsons in 1954, "but not a superficial beauty—a very deep longing for a uniting of lost parts." According to Bess' view, the paradigm for this lost wholeness had its basis in an imaginary period of androgyny, before the bifurcation of gender—of a distinct maleness versus a distinct femaleness—came into existence. the notion that this wholeness could be retrieved through an actual tinkering with sexual organs, such as Bess arranged for himself, seems like an inconceivably brutal assault on the self. Yet to write it off as mere pathology seems to me to be underselling the poignant radicalness of Bess' vision, one which expresses in extreme, even purist form the yearning for unity that we all possess in our splintered, everyday lives.

"Among American Modernists," writes John Yau in his excellent essay on the painter, "Bess belongs to the tradition which fights to reinvest symbols with meaning." Because Bess believed that he was the carrier of the images he produced on canvas rather than their creator, his symbols seem to writhe and implode with a kinetic energy, one that promises to offset our own daily tensions and offer in their place a diagrammatic resolution of opposites. These are the scratches and squiggles of a holy innocent, a blessed misfit of a fisherman who saw things, in his own words, "otherwise than by ordinary sight" and thereby saw the world as it might be rather than how it is. |

||||||

This photo of Forrest Bess dates from 1951-52. He is holding Molly Heubner's Chihuahua. Molly was an early mentor of Forrest's and the wife of John Heubner; theirs was a prominent family in Bay City and Matagorda County. Molly lived mostly in Houston after their children were grown and commuted occasionally to Bay City. This photo of Forrest Bess dates from 1951-52. He is holding Molly Heubner's Chihuahua. Molly was an early mentor of Forrest's and the wife of John Heubner; theirs was a prominent family in Bay City and Matagorda County. Molly lived mostly in Houston after their children were grown and commuted occasionally to Bay City.

In 1951-52, I worked for Molly in Houston publishing a weekly folder called "You're in Houston." She owned properties in the Montrose section; one was an up/down duplex where I lived upstairs and Forrest lived in a rickety garage apartment in the back for a year or more, when he was in Houston, which was frequently. In that timeframe, Forrest was a perfectly nice, congenial guy and fun to talk with. Nothing too bizarre had gotten him by the foot yet. However, he did have a theory about the color pink, that it was highly motivating to people. He had just finished an exhibit where he positioned a painting featuring large blocks of pink right before the entrance to the restrooms and kept a watchful eye on how many people entered the restrooms immediately after viewing that painting. He found his little experiment highly amusing and was certain that it validated his theory. During this same time, Forrest also had artistic dealings with Lincoln Kirstein, whom he talked about now and then.

|

||||||

|

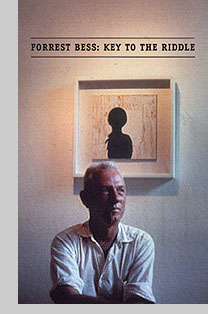

The following was contributed by Chuck Smith, producer and director of "Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle." In 1988, I walked into a roomful of paintings that changed my life. It was a 60-painting Forrest Bess retrospective at Hirschl & Adler Gallery in New York. The opportunity to see that many Bess paintings in one place at one time was a very rare occurrence and hasn't happened since, and while I didn't know that then, I could tell that I was in the midst of something weird and wonderful. The paintings were small, striking, and completely unpretentious. Each canvas seemed familiar, though I knew that I had never seen any of the images before. The other odd thing was that I couldn't guess whether they were painted recently or fifty years ago; they seemed timeless. I took the catalogue and went home. From the catalogue I learned that Bess had already been dead for ten years. I also learned that he was a bait shrimp fisherman from Texas, and that he had devised a grand theory involving symbolism, androgyny, and immortality. I wanted to learn more, but I was too busy working.

We learned a lot more about Bess than any film could contain, but there were also some missed opportunities. Some of Bess' best friends had already passed away, and an audio interview that someone had done with Bess in the 1970s had been borrowed and never returned. And, of course, a full copy of Bess' infamous thesis has yet to surface. But, in the end, a look at a person's life is always selective and it is up to the viewer or reader to figure out who that person was. Forrest Bess left many clues to his existence, and the documentary is a collection of those clues . . . a "key to the riddle." Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle is distributed by and can be ordered from the Checkerboard Film Foundation. To view a preview clip, visit Chuck Smith's Forrest Bess YouTube page. "Narrated by actors Ruth Maleczech and Willem Dafoe (the voiceover for Bess), this video skillfully interweaves interviews with those who knew the artist; commentaries by scholars and curators; film footage; stills; and Bess' own writing. This documentary does a superb job of describing how this outsider from Texas achieved insider status in the New York art scene."—Library Journal, March 2002 |

||||||

|

The following was written by Jim Scarbrough, whose family owned a cabin in Chinquapin, near Forrest Bess's home.

We lived in Pasadena, Texas where my step-dad owned a plumbing business. As the friendship grew, Forrest occasionally would visit us at our home. He would sit on the floor with my sister and me and play jacks with us. He always seemed to think a lot of us kids. He liked to discuss his visions and dreams with my family. He once even painted a canvas of a dream that I had discussed with him. However, I never saw it as he sold it soon after it was finished. Forrest lived alone before and after his parents died and would get very lonely and drank quite a lot, but always had a good sense of humor and was always pleasant to be around. After his dad died, he frequently visited his mother in Bay City until she died. He lived with her for a short time, but I am not familiar with that part of his life. He was seldom seen when he wasn't smoking his pipe. He was always broke and Mom and Dad would loan him money to help out. Forrest would paint a canvas for them now and then and always said he would buy them back some day, however, he never did. He always told my folks not to get rid of the paintings because when he got famous, they would be worth a lot of money. He said then that he knew it would not be in his lifetime. "That's just the way it is with 'great' artists," he'd say.

Forrest caught and sold shrimp to support his artist's lifestyle. He did sell many paintings during his life, but never made enough to support a more normal life. Occasionally, he would have someone help him with the shrimping, but I am sure he was never able to pay them enough to keep them happy. However, he seemed to be happy doing what he did, even when it was just him alone. He liked his privacy. I know he always made me feel welcome when I was there. He always fixed me up with a cane pole and some shrimp to fish in the Intercoastal for redfish. I nearly always caught fish doing that. My mother would always get some shrimp and go to the point and catch some nice flounder. I know very little about his education except for the fact that he attended several different universities and colleges. He was a very intelligent man and I admired him for that. My mother kept a scrapbook on him and we kept it after her death until recently. I always knew he was a strange person, but I personally never witnessed some of the negative traits that came up about him after his death. He was a good, caring person as long as I knew him and that's the way I prefer to remember him.

|

||||||

Six years later, I saw the catalogue in my bookshelf and reached for it. There were the paintings again. This time, I was ready to learn more. I visited the Archives of American Art and began reading the letters of Forrest Bess on microfilm. Fortunately, Bess lived in an era when letter writing was crucial for a man who lived in a remote part of Texas. Bess' letters to Betty Parsons, Meyer Shapiro, Carl Jung and others are an amazing peek into the mind of an artist who truly believed that art could save his life. As a filmmaker, I immediately saw Bess' life as a documentary, and quickly planned a trip to Texas to start shooting. My friend, the artist and cinematographer, Ari Marcopoulos, and my wife, the artist and soundwoman Sono Kuwayama, joined me. In Texas, we set out to find every painting we could and to interview as many people who knew Bess as possible. The first thing we noticed was that Bess had a wide range of friends from simple fisherman like Roy Vosloh to well-known artists like Amy Freeman Lee. They were from completely different worlds, but were united in their admiration for Bess and his work. The final film could only include about half of the wide range of people we spoke to. I was sad to leave out a sincere and revelatory interview with Bess' only brother, Milton. I also had to skip a great story that the artist Agnes Martin told of going shopping in New York City with Forrest. It seems their dealer, Betty Parsons, wanted to get Bess out of her hair while she installed his show, so she asked Agnes to take him coat shopping.

Six years later, I saw the catalogue in my bookshelf and reached for it. There were the paintings again. This time, I was ready to learn more. I visited the Archives of American Art and began reading the letters of Forrest Bess on microfilm. Fortunately, Bess lived in an era when letter writing was crucial for a man who lived in a remote part of Texas. Bess' letters to Betty Parsons, Meyer Shapiro, Carl Jung and others are an amazing peek into the mind of an artist who truly believed that art could save his life. As a filmmaker, I immediately saw Bess' life as a documentary, and quickly planned a trip to Texas to start shooting. My friend, the artist and cinematographer, Ari Marcopoulos, and my wife, the artist and soundwoman Sono Kuwayama, joined me. In Texas, we set out to find every painting we could and to interview as many people who knew Bess as possible. The first thing we noticed was that Bess had a wide range of friends from simple fisherman like Roy Vosloh to well-known artists like Amy Freeman Lee. They were from completely different worlds, but were united in their admiration for Bess and his work. The final film could only include about half of the wide range of people we spoke to. I was sad to leave out a sincere and revelatory interview with Bess' only brother, Milton. I also had to skip a great story that the artist Agnes Martin told of going shopping in New York City with Forrest. It seems their dealer, Betty Parsons, wanted to get Bess out of her hair while she installed his show, so she asked Agnes to take him coat shopping.