|

||||||||

In this ramshackle cabin on a backwater bay of the Gulf lived and worked one of the greatest artists Texas has ever produced. "His Name Was Forrest Bess"

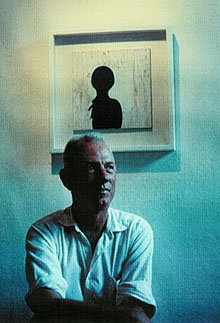

Forrest Bess died five years ago, a victim of old age, alcohol, and his own maddening vision. But he is still easily conjured up by the fishermen of Chinquapin and the citizens of Bay City, the small town twenty miles to the north where Bess was born and raised and where he died. To these people Forrest Bess was an exemplar of that legendary, cherished, and vilified figure, the small-town eccentric. The memories they have form around his contradictions: a gangly, tousle-haired, khaki-clad outdoorsman who was given to passionate discourse on Jung and Goethe; a marginally existing bait fisherman who proclaimed himself driven by a mysterious intelligence of momentous importance to mankind. He was a valued friend to some and a pariah to others, a sensitive, admired artist surrounded by murky, disturbing rumors. Forrest Bess didn't quite fit, and he spent most of his life reaching out to a wider world that he hoped would understand him. But he remained a part of Bay City, was tolerated, accepted, and nurtured there; and in the end he realized that he could be at home in no other place. Unlike most small-town eccentrics, Bess left a legacy far more remarkable than memories and decaying landmarks. In addition to dozens of small, baffling, and oddly beautiful canvases that he painted at Chinquapin, he left behind hundreds of letters. This correspondence has been collected by the Houston branch of the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art and has had considerable impact an the artists and art historians among whom Bess is becoming a cult figure. But it is also more than a collection of documents of sudden scholarly import. It is a rare chance to sound the depths of one of those almost stereotypical small-town characters, to listen to the secrets that he felt set him apart from everyone else. It is an invitation to an autobiographical journey that begins on the South Texas coastal plains and ends in an intellectual landscape so bizarre, frightening, and elaborately constructed that only its creator could possibly imagine it. Forrest and I grew up together in Clemville, which was a very busy, busy oil field and boom town. There were three or four stores, a rooming house, and a pool hall. I remember lots of mud—nothing but mud—and sidewalks made of wood.

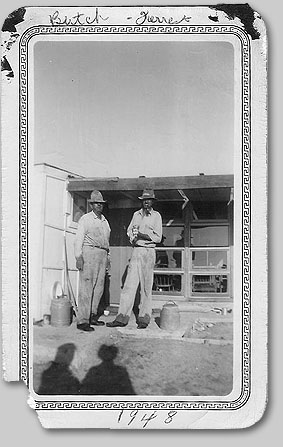

Forrest also had visions. As an adult, he wrote vividly of his first one: "It was on Easter morning—I woke up and looked at the spool table before the window. The sunlight was striking a cutglass vase of my Mother's. I looked at the table itself and there on the table was a little village—cobblestone streets, a town well, people walking about and the sky full of refracted colored lights from the sunlight. I got out of bed to go over to it but I happened to look at the chair next to my bed and there sat a tiger—I moved away to edge up to the table from the other side but in another chair next to the table there was a lion—so naturally unable to get to the vision I let out a squawk and here came the family from the kitchen. I was four years old but the vision has always been brilliant in my mind." When he was seven he saw his first oil paintings, which had been done by a neighbor who was a china painter, and shortly thereafter he began to make pencil copies of pictures from the encyclopedia. Later he started reading Greek and Roman mythology avidly, and he tried a crude oil-on-cardboard painting of the Discus Thrower. When he was thirteen, he took his first formal lessons in oil painting, from a neighbor in Corsicana; he copied a view of Yosemite Falls and a Dutch boat scene. "The art was the refuge," he later wrote. "The impractical dreamland." By the time Forrest came back to Bay City and entered high school, his personality seemed to be pulling in two directions. He was a brilliant student, played on the football team, and attended dances and other social gatherings, but he always seemed to be somewhat withdrawn, as if off in his own little world. He worked in the oil fields but dreamed of mythological heroes, Greek temples, and the ancient cities of Mycenae and Troy. Forrest was fond of both his father, a big tobacco-chewing high roller with a sixth-grade education, and his mother, a slender, lovely woman who adored and was sympathetic to her son. But there was friction when Forrest graduated from Bay City High School. He wanted to study art in college, but his parents wanted him to go to West Point. I was valedictorian of our high school class, and Forrest was the salutatorian. He was tall like his mother, who was tall and stately, but Forrest was loose-jointed, almost an Ichabod Crane. He was anything but good-looking. At that time in our lives everyone desperately wanted to conform—you wouldn't dare to be different. But not Forrest. In fact he prided himself on being different. We used to tell him that he wasn't one of the group, that he wasn't a regular guy. He would say, "Well, that is the mark of a genius," and we would just laugh and laugh. To his family's utter dismay, Forrest flunked the West Point exam because of a curvature of the spine and, he said, his stutter. He still wanted to study art, but he settled for a compromise with his family; he would go to Texas A&M and study architecture, which was considered manly and practical. After two years, Bess decided he was entirely unsuited to architecture, a failure, and in 1931 he transferred to the University of Texas. There he spent hours in the libraries poring over books on religion, psychology, and anthropology. He also started to have vague doubts about his sexual identity—a concern that would return with profound consequences later in his life—and he read and reread Havelock Ellis's Psychology of Sex, at the time an innovative survey that frankly discussed sexual fetishes and suggested that homosexuality be politely ignored as simply another form of bad manners. While Bess was at college his family in Bay City was riding the roller coaster of the oil boom. About the time Forrest entered A&M, Butch Bess sold his half of an oil lease he owned with R. E. "Bob" Smith for a reputed $100,000, an enormous sum at that time. Smith went on to become one of the richest men in Texas, while Butch bought an expensive car, gambled, drank, chased women, and rapidly squandered his fortune. Soon Forrest's father went broke. The family's main source of income was three rent houses and a vacant lot in Bay City that Minta Bess had bought. By the early thirties Butch was running a bait fishing business at Chinquapin, where the family had visited in Forrest's childhood, to supplement their income. Bess dropped out of college in 1932 and went to work roughnecking in the Beaumont oil fields. Like many people during that root-wrenching, restless decade, he would work for a few months, save money, and then wander. In 1934 he made the first of his periodic trips to Mexico, where he lived on $10 a month and watched the renowned Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera at work. Six months later he returned to Bay City and built his first studio. In 1936 he had his first one-man exhibition in a Bay City hotel. Along with his paintings of people, houses, and dogs he exhibited some works in a fledgling van Gogh style. There were also a few less identifiable, rather abstract paintings based on symbols that seemed to dart into his consciousness when his eyes were closed. That exhibit was followed by one-man shows at the Witte Museum in San Antonio and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston in 1938. Bess was even included in the biennial exhibition of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. But he continued to roughneck and wander in near-destitution, until in 1941 the United States went to war, and Forrest Bess found himself caught up in the conflict that would change his world forever. He enlisted as a private and, like many artists, was assigned to design camouflage. Bess threw himself into his work and rose to the rank of captain in the Corps of Engineers. But with the winding down of the war, his project was shelved and he was sent to MacDill air base at Tampa, Florida, to teach bricklaying. The lack of responsibility and challenge in his new duties frustrated Bess, and one day his colonel bawled him out because of his attitude toward his class. Bess left the colonel's office, and just as he closed the door he said out loud, "Why, you damned smirking hippopotamus." Bess went back to his hotel and went to sleep. During the night he had another vision, which he described in his letters a few years later. He awoke crying and "fell through my bed in the hotel into a yellow room with two horrible animals—one a fuzzy horse teeth showing and blood red eyes the other a hippo with eyes almost closed and an unbearable stench—both were nodding their heads." Bess packed his belongings and took a taxi to the base. On the way, he felt as if his entire body were being flushed away from the inside with hot water. At the base's mental clinic he was given a sedative. Afterward, he had two more visions. He was granted a leave of absence and cried for hours at a time over a period of three or four days. He described his whole world as turning yellow-amber. "And it could have been about this time that I separated the mind and the body," remembered Bess. "The mind could be given free reign unfettered. It had unlimited visions." After his breakdown Bess asked his colonel for permission to see the base psychiatrist. He was refused, but he went on his own. Finally he requested a transfer to a convalescent hospital as a painting instructor. This time his request was granted. Bess completed his occupational therapy and left the service. He settled in San Antonio, set up a small studio, frame shop, and gallery on Villita Street, and joined San Antonio's burgeoning postwar art colony. He was a distinctive figure, always wearing his khaki Army pants and his close-cropped military haircut. He could he moody and acerbic, but he also had a wry sense of humor and frequently attracted gatherings of artists and musicians at his studio. He participated in a number of local exhibitions, and his work started to move away from his van Gogh style to the simple abstract symbols that he had experimented with in the mid-thirties.

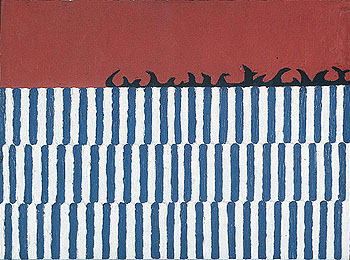

By the time he settled at Chinquapin, Bess had entirely repudiated his previous efforts as an artist. "God I can remember," he wrote, "hours—days months and years spent sitting at an easel staring at a blank canvas—trying to be successful—criticizing my own efforts—aping this master or that master. Thinking their thoughts. Hiding from myself through fear, that source which was pounding for recognition within my own being. And then when I relaxed from the effort I was aware that here it was." Bess turned his attention to "that source," which he identified as the real author of his now regularly recurring visions. They were not elaborate visions, like the Dutch village or the grotesque animals he had seen at the time of his mental breakdown, but crude abstract shapes that seemed to appear on the inside of his eyelids just after he awoke in the middle of the night or in the early-morning hours. Bess found that he could not summon the visions and that they could frequently elude his attempts to record them on the sketch pad he kept by his bed. "I have no control over the duration of the vision (I'm lucky if I have time enough to make a sketch in bed). The only thing I do have is a choice as to which one I will sketch. One night they were all in black and white and happened (changed) so quickly that I sketched and painted only one." Bess also discovered that any of the visions that he didn't copy would be lost forever, his conscious mind was simply unable to retain them. Bess couldn't explain these symbols. They were often just circles, crescents, checkerboards, or rows of lines, sometimes floating in vague atmospheric backgrounds. What they resembled more than anything else was the simple vocabulary of abstract symbols used by Paleolithic cave painters, but at the time, Bess was unfamiliar with the cave paintings. He could only acknowledge that his source was a special gift—"You know, I am a very fortunate person I guess. This source of mine is remarkable in that the effort to create is gone"—and that he was obliged to follow it faithfully. "I cannot bring myself around to the point of adding to, taking from, elaborating, or making into a picture—these visions that I have. To do so would be hypocrisy and untruthful. Many times the vision is so simple—only a line or two—that when if is copied in paint I feel 'well gosh, there isn't very much there is there?' I do not think that I could live with myself at all if I added to the vision." As Bess turned out small, distinctively colored paintings of his visions, he began to understand the process of creation, if not the meaning of the symbols. He felt that he was "a conduit through which they pass and are put on canvas" and that his conscious mind was now totally divorced from the act of painting. It was a realization that filled him with excitement and dread. Perhaps these symbols from an unknown source could help him uncover his own identity, a process he regarded with ambivalence. He also began to wonder if his quest was linked to a much greater discovery that could benefit all mankind. Bess started looking for a wider arena for his paintings. A year after moving in Chinquapin he sold off forty of his older paintings for $10 each and took a trip to New York to visit galleries and look for a dealer. Back then there were merely dozens of art galleries rather than the hundreds that glut Manhattan today, and Bess seems to have gone from door to door until he had visited every gallery in the city. It would have been hard to tell at the time—even for the artists and dealers involved—but the war that had changed the political balance of the globe had also shifted the axis of the art world. Many esteemed European painters, from Mondrian to Max Ernst, had found refuge in New York from the Holocaust. Perhaps the most influential were the surrealists. Important American abstractionists, like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky, began to employ surrealist techniques to invent symbols that suggested primordial life forms, anatomical parts, ancient mythic symbols, and Indian totems. But by the late forties most of them had pushed beyond these somewhat hackneyed symbols toward highly simplified abstractions. And the feelings represented on those huge, emotively brushed canvases were generally those of psychological or metaphysical anxiety; as Rothko put it, "Only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless." So began the fabled movement known as Abstract Expressionism, a movement that had at its core a belief shared by Forrest Bess: that the individual painter could put fundamental truths on canvas. At the time Forrest Bess was making his rounds in New York, however, the abstract expressionists were a neglected group of radicals shown only in a few avant-garde galleries. Bess, whose work was equally outré, soon decided that the only galleries advanced enough for him were the hotbeds of the new movement. He particularly liked the Betty Parsons Gallery, where Parsons was assembling a stable of some of the more celebrated abstract expressionists: Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Pollock, and Rothko. Parsons was warmly receptive to Bess and agreed to take his work, and he returned to Chinquapin to continue painting. But the idea of showing in New York filled him with anxiety. He worried that his work would not sell and would become a liability to the gallery. He wrote to Parsons regularly, and if he did not hear from her for a while, he worried that he was being laughed at. He also did not have the training in or concern for the formal aesthetic issues that preoccupied most of the abstract expressionists, and he began to feel like an outsider's outsider. He even wondered if his ideas were merely the rantings of a madman. By mid-1949 Parsons had assembled enough of Bess's small canvases to schedule a one-man show for December. Several months before the show opened, Bess went to Woodstock, New York, to stay at the farm of Sidney and Rosalie Berkowitz; Rosalie was a painter and friend from Bess's Villita studio days, while Sidney had been a part owner of Frost Bros. in San Antonio. There was nothing eccentric in the way Forrest looked at all, nothing wild-eyed about him, nothing really outstanding. He was very close to our cook, a marvelous black woman named Lucinda who had worked for us for thirty-five years. We had a large country kitchen with a big table in the middle, and he would sit down at that table and have discussions with her. Forrest and my husband were very close, and they would have long philosophical discussions on art and life. I was the only person he ever fought with, because I disagreed with the things he said. Whenever we were together he would talk about painting. He would tell us how he worked, how he kept the note pad by his bed, and how he would see the images on the back of his eyelids and make little sketches of them. He always said he had no idea of what they meant. At Woodstock Bess met Meyer Schapiro, an eminent art historian who seemed genuinely interested in Bess's art and his search for its significance. Shortly afterward, Bess described the meeting: "The hour and half that I spent at Meyer Schapiro's was one of the most interesting and exciting times I have ever had. It was sort of like being in a skiff with a good friend in the bay—no wind—purple haze—not a ripple on the water—a feeling of good companionship." Bess considered his first New York show a success; he received favorable reviews but, as he expected, did not sell many paintings. He had enjoyed his stay in bucolic Woodstock, but by the time he left New York City he was ready to return home. The city gave him "nerves in the stomach," and he did not enjoy the company of so many other artists. He suspected that they thought him a hick, while he adopted a disparaging view of what he regarded as their stylistic conceits. In his eyes the paintings of the abstract expressionists were simply concoctions, and he angrily dismissed their art-for-art's-sake approach: "Painting itself is of no more advantage of no more importance than the hand is to the mind. It is a means! A way. Nothing more. A way to find a truth." Back at Chinquapin Bess found himself again under the hypnotic, almost mystical influence of the Gulf. "The peninsula is a lonely, desolate place," he wrote, "yet it has a ghostly feeling about it—spooky—unreal—but there is something about it that attracts me to it—even though I am afraid of it." He was now determined to stay. He built a shack on a concrete slab using the hull of a tugboat and copper sheets from the bottom of an old ferry, and he added a slanted concrete "prow" to his little home that would, he hoped, withstand the battering of hurricanes. He continued to fish for a living and to record and paint his visions. He also began to decipher his symbols.

"I never felt such a sense of loneliness, of desolation. Nothing alive but me. So long, long ago. So ancient, beyond memory." This vision in the summer of 1953 became the pivot on which the rest of Bess's life turned. It was the climax of several years of intensive painting, reading, and writing, and after it Bess's relatively benign curiosity about his symbols became a reckless, all consuming, and tragic passion. The vision had an elaborate but, to Bess, convincing explanation that began with the work of the Swiss psychiatrist Carl G. Jung. From Jung, Bess adopted the theory that civilized man had divorced his unconscious mind from his conscious mind and as a consequence suffered tensions, neuroses, and psychoses. Bess then followed Jung's assertion that certain archetypal symbols could stimulate the reunion of the conscious and unconscious minds, creating a primal state of psychological bliss that would release modern man from the tensions of his overrationalized existence. "I just feel," wrote Bess, "that the mass of people are living in a darker world than they need to live in." Bess theorized that the symbols—specifically the rows of vertical lines—in the painting that he had stared at that summer night had brought him to some primordial state of consciousness. But unlike Jung, who described the return to man's primal state of consciousness as a psychological or spiritual probing of a collective unconscious, Bess was convinced that he was actually reliving the physical experience of his "Self" in the distant past. He believed—or desperately wanted to believe—that his painted symbols had the power to activate the deathless memories of an eternally existent and psychologically untraumatized Forrest Bess. Painting, he concluded, was "the Great Means through Therapy in which the individual may be come keyed into the Eternal." Undaunted by the magnitude of the role he now assigned his art, Bess continued to paint and went to work assembling a detailed vocabulary of his universal, therapeutic symbols. He corresponded with a number of psychologists and doctors—including Jung—who he thought might be interested in his theories, insisting in his letters that the artist, with his ability to release tension via his symbols, could benefit modern man far more than science or medicine could. It was a claim that he took very seriously, and he realized that if his distinguished correspondents were also to take it seriously, they would require some proof. That really wasn't a problem, because Bess had already fixed on a highly suitable guinea pig for his therapeutic transformation. That guinea pig was Forrest Bess. There's usually a good deal of tolerance for eccentrics in small towns. Forrest designed crab traps and a hurricane-proof roof, so he was considered to be useful. My mother and her friends appreciated his ability as an artist and encouraged him by commissioning portraits. His dream work was not well received, however. My parents—who were very square—enjoyed visiting with Forrest at his camp at Chinquapin; they would sit and talk and drink Forrest's strong, dark coffee, which looked like it had been brewing for three weeks. On one visit to Chinquapin, Forrest started talking about his correspondence with Jung. I guess he thought that I would know who Jung was and be impressed, and at first I was. He said, "Jung is very interested in my ideas." Then Forrest squinted his eyes and puffed his pipe, looking very profound, and added, "Something he said reminded me of the fourth canto of Goethe's Faust." At that point, I became skeptical. I felt like he had grandiose intellectual pretensions, and I eventually learned that you had to discount a great deal of what he said, but he was always interesting to talk to. Bess had long been aware of two conflicting tendencies in his makeup, and although he did not consider himself schizophrenic, he did refer to them as "personality #1" and "personality #2." Number one was "the typical Texas ambitious man. Rather roughshod." He was the roughneck, the fisherman, the captain in the Corps of Engineers, "practical—masculine—sensible—displaying leadership—aggressive." Number two, by contrast, was "as weak as a jelly fish." To Bess, this personality seemed "quite helpless in relation to adjustment to society. It is artistic—sensitive—introspective and had rather cry or lament the shortcomings of mankind rather than fight. . . . This personality I have found is actually somewhat effeminate." Bess believed that the integration of his two personalities would reunite his conscious and unconscious minds. He even surmised that the unconscious minds of all males were effeminate, while the unconscious minds of all females were masculine. The ideal human being would, in Bess's interpretation, bring together the characteristics of both sexes. His prodigious research soon provided Bess with all sorts of arcane and sometimes surprisingly logical connections between androgyny and the freeing of modern man. Through his imaginative, undisciplined scholarship, Bess concluded that the pancultural theme of art throughout the ages was the hermaphrodite. By the mid-fifties Bess had become too intoxicated with his theories to settle for a sweeping cultural investigation and its attendant conclusions. Still anxious to challenge the modern scientist and doctor, he began to explore the medical implications of his research. He took as a starting point the experiments of Eugene Steinach, a thoroughly discredited researcher (which merely added to his cachet, in Bess's estimation) who claimed to have arrested aging and rejuvenated men and animals by tying off the vas deferens, thereby causing the flow of semen to back up and create pressure on the interstitial cells that Steinach insisted produced the male hormones. Spurred by these claims, Bess began to study anatomy and endocrinology texts. He planned to devise a procedure for creating a pseudohermaphrodite with characteristics even more unusual than the combination of both sexes in one body. It would be the prototype of a perfect race of human beings reunited with their unconscious minds and so free of psychological tensions that wars and prisons would cease to exist. And because of effects similar to those produced by Steinach, Bess's pseudohermaphrodite would also be immortal. The man who was formulating these theories throughout the fifties continued to paint and fish for a living. By now he was a fixture at Chinquapin, heading out to the bay in his sixteen-foot skiff with an outboard motor on the stern and "Bait" in big letters on the bow. His cluttered studio was a local landmark and now featured a refrigerator, stove, typewriter, and a layer of oyster shells on the roof for insulation. Bess himself was a colorful, almost romantic figure: tall, mustachioed, with blue eyes, a tanned face, and a shock of nearly white hair, and always those khaki pants. He was a legendary raconteur who clearly enjoyed entertaining—and shocking with excerpts from his complex theories—the cronies, artists, reporters, and occasional patrons who visited him in a steady trickle. But life also had its predictably dark side for Bess, marked by the long, dreary winters of idleness, poverty, and morbid self-contemplation. Although Bess earned only a marginal living from the combination of fishing and art (he estimated his sales of art at about $200 a year), his reputation continued to grow. In addition to regular shows at the Betty Parsons Gallery, his work was displayed in one-man and group museum exhibitions all over the country. He had also developed a following in Houston and had an attention-getting one-man show at Houston's André Emmerich Gallery in 1958. But Bess accepted his local notoriety almost as a matter of course; his real work was of such immense importance that merely becoming an artistic celebrity could hardly reward it. He continued to wage what he described as a "tremendous battle through correspondence" with almost any expert he thought might be interested in his theories. He compiled a notebook of sketches, clippings, quotations, and other data that might corroborate his theories. He also produced a step-by-step manifesto based on an obscure manhood rite practiced by Australian aborigines, which involved the mutilation of the male genitals. "All symbolism in art," Bess wrote in his treatise, "points towards this mutilation as being the basic step towards the state of pseudo-hermaphrodite as the desirable and intended state of man." The manifesto dropped like a dark curtain between Bess and his closest intellectual companions. Meyer Schapiro dismissed it and Bess called him a chained slave. Betty Parsons declined to hang what he called his manifesto as a show, and he wrote her angrily in 1959: "Art to me is the search for truth so death will end. To you it is a matter of aesthetics." But Bess was, strangely, given hope by Jung's final reply to all his correspondence, entreaties, and theses. "What you have found is not unique," wrote Jung. "It has been found possibly once each century since the beginning of time. It invariably leaves the individual with the feeling that they have made The Great Discovery. Let us return to the safe basis of facts." To Bess, the ancient history of his thesis indicated its timeless significance, and as for "the safe basis of facts," that was all right for Jung. Jung, after all, wasn't an artist. Jung was just scared. Inflamed by rejection, excited by the prospect of going further than even Jung had dared to go, and drawn on by his own terrifying logic, Bess decided in 1960 to take the next step in proving his theories. The events of the night on which Forrest Bess became a pseudohermaphrodite are clear. According to Bess, he paid a local physician, Dr. R. H. Jackson, $100 and several paintings to perform the necessary surgery. Sex researcher Dr. John Money later corresponded at length with Bess and concluded that Bess, who exhibited an extensive knowledge of anatomy, medical procedures, and painkilling drugs, had operated on himself and invented the doctor's participation to legitimize his experiment. Other possibilities are that the doctor, who apparently did attend Bess on the night in question . . . Jackson died shortly after supposedly performing a second operation on Bess in late 1961. The anatomical facts, however, are clear. In accordance with the aborigine ritual, an opening, or fistula, was created beneath Bess's penis at its junction with the scrotum. This opening led through an incision in the urethra to the bulbocavernous urethra, a naturally enlarged section of the urethra that Bess insisted was capable of intense orgasmic stimulation. According to Bess's theories, the bulbous section of the urethra could, if sufficiently dilated, receive another penis in what would be the ultimate, eternally rejuvenating form of sexual intercourse. The years just following his surgery were a time of bitter disappointment for Bess, punctuated by extravagent hopes. Fishing became less and less profitable, and Bess was weary of waiting for the shrimp to come in each spring before he could pay his modest bills. In September 1961 Hurricane Carla ran right over Matagorda Bay, generating a sixteen-foot tidal surge that washed the entire community of Chinquapin over fifty square miles of surrounding pastureland. Only the concrete prow and slab of Bess's studio remained. Bess, however, proud that he was a Texan "determined to conquer land and water," slogged through the mud picking up his scattered belongings and began to rebuild. Bess also began to rebuild the friendships that were now recovering from the shock of his manifesto and his horrifying operation (he even sent pictures of the alterations to Petty Parsons). Parsons gave Bess a retrospective exhibition in 1962, and Meyer Schapiro wrote the catalog essay, in which he commented: "Forrest Bess is that kind of artist rare at any time, a real visionary painter. He is not inspired by texts of poetry or religion, but by a strange significance in what he alone has seen." Bess's work once again received good reviews but did not sell well, and he had more reason than ever to be bitter about the mild interest in his art. In the fifteen years that had passed since he first took his work to New York, Bess had seen the despised abstract expressionists become an international institution and the recipients of unheard-of sales figures for modern painting. Bess was convinced that the hated Rothko, Still (whom he accused of copying his paintings), the late Pollock (Bess had once stormed out of a showing at the Parsons gallery after Pollock began one of his "artistic tirades"), and most of the other artists of the "concoction school" were self-exploiting and insincere; their success was proof of that. Bess in turn saw that his lack of recognition reflected a cultural schism. "I would dare the critic who reviewed my work to sit at home some night just with one small insignificant canvas of mine and look at it and nothing else for a period of thirty minutes or longer. I can make them cry for the loneliness they feel. . . . Don't sell the magic packed in the canvases short. But again reflection is needed for the integration of the ideogram and I am not sure New Yorkers have that much time to spare. Go-Go-Go!" But Bess did not give up on his quest for truth and vindication. In late 1962 he began to correspond with the controversial sexual psychologist John Money of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Money, who later reported on Bess in a paper titled "Three Cases of Genital Self-Surgery and Their Relationship to Transsexualism," encouraged Bess to disclose the details of his theories, his surgery, and his sex life. While Money's interest was clearly clinical, Bess saw this correspondence as the chance to finally "take the human body away from medicine and give it back to the artist." When not writing to Money, Bess continued to proselytize through more conventional means. He planned a film about Dionysus as man, god, and bull (Dionysus, who emerged from the thigh of Zeus, was another of Bess's favorite themes). He had a rather successful show at Kathryn Swenson's New Arts Gallery in Houston in 1963, and his popularity in Houston increased throughout the sixties. Not only did important local artists, like sculptor Jim Love and sculptor-filmmaker Roy Fridge, find Bess fascinating, if somewhat frightening, but many of Houston's most prominent art collectors showed an interest in his work. John and Dominique de Menil and Nina Cullinan were longtime Bess patrons, as was Dallas's Stanley Marcus. Other collectors included George Brown, Houston architect Howard Barnstone, and Barnstone's New York colleague Philip Johnson. But Bess only grudgingly sold his canvases—he once said he wished they could all be kept together as a collection—and his favorite collector was a Pasadena plumber named Jack Akridge, who bought fourteen of Bess's paintings at $10 down and $10 a month. The only way you could get to Forrest's—or back—was if he took you in his boat. He'd cook up some strange sort of shrimp-crab stew that would be bubbling up on the stove, and you thought you were taking your life in your hands just eating there, but it always tasted great. His personality was so powerful that you wondered what he was going to do next. Bess's big secret remained just that to most of the people in Houston and Bay City who knew him. His friends admired his sincerity as an artist, even if what they heard of his theories—which Bess revealed in their entirety to only a select few—sounded pretentious and unappealing. Bess never gave any outward sign of his sexual orientation and protested to his correspondents that he hated effeminate men and that his theories really had nothing to do with homosexuality. Word did leak out occasionally, and Bess once mentioned a homosexual ex-friend who told stories about him and made it impossible for him to go to local bars anymore. But Bess's real frustration was his growing impatience with Dr. Money, who was obviously not going to help him prove his thesis. The late sixties and early seventies were an agonizing coda to Bess's long search for the truth. He had always worried that he was "suffering from some sort of mental disease that may be contagious" and conceded that "the Creator behind me may be the Devil or it may be Dionysus." Now that it was apparent that Money, too, was unconvinced, the tenuous threads of logic that had held Bess's theories in a presentable, if debatable, form finally dissolved. Physical and emotional stress also played its part. In 1966 Bess had to have part of his nose, cancerous from all his years in the sun, removed and then had to undergo reconstructive surgery. His skin cancer forced him to retire from Chinquapin to one of his mother's houses in Bay City, and the move was painfully disorienting "Adjustment to living in town has not been easy for me. I miss my little yellowed egret that rode my old cypress skiff. I called the egret George. He could locate me out in the bay where I had gone to trawl. He always landed on the boat, looked at me, in fact even while perched on the edge of the boat well he kept one eye on me. Large black pupils and yellow irises." Two years later, the medical editor of the Washington Star lost the notebook that Bess had been compiling for ten years, although Bess suspected that it had been destroyed because it was too dangerous to publish. A year after that, his mother died. He applied for a veteran's disability pension and was denied. He drank heavily. In his last active years as an artist, Bess began work on a large panel painting based on his Dionysus and the bull theme. He began to suggest that someone recommend him for a Nobel prize for his original research. And throughout 1973 he was supported by a grant Meyer Schapiro arranged for him; the funds came from a foundation endowed by a gratefully wealthy Mark Rothko for the care of older, impoverished artists. In late 1973 and early 1974 Bess began to act strangely in public. He got into trouble with the law on one occasion for apparently causing a scene in a hobby shop, although he could not remember the incident. Several months later he was arrested and jailed for wandering nude on a city street late one night, and again he had no memory of it. He was committed to the San Antonio State Mental Hospital, where his condition was diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. After a few weeks Bess was transferred to a Veterans Administration hospital in Waco and then to the Bay Villa Nursing Home in Bay City. Nothing more was heard of Bess until the Bay City Art League gave him a one-man show in March 1977. At his opening, he appeared alert and lucid and happily discussed his theories. Eight months later, on November 11, Forrest Bess died of a stroke, and his dreams of immortality ended. His body, as he had wished, was donated to medical research. There are myriad explanations for the strange life and times of Forrest Bess. Insanity, repressed homosexuality, alcoholism, and an instinct for sheer sensationalism figure prominently among the more skeptical or less charitable interpretations. To sympathetic eyes he could even be seen as a troubled genius, an innocent burdened by an overwhelming gift. But perhaps he is best described as a man out of place in time, a passionate, intensely metaphysical thinker who in a less rational age might have been a celebrated ascetic, a famed doctor of the church, or an esteemed pagan philosopher. His visions—which clearly were real to him—belonged to the great body of history that we have largely put behind us, when voices from the sky built mighty empires and jury-rigged philosophies established enduring faiths. In terms of his art, however, Bess was fifteen or twenty years ahead of his time, a miss that today is as good as an eon. He was not the only artist to accuse the abstract expressionists of throwing their angst around with a little too much finesse. A Port Arthur native named Robert Rauschenberg—fourteen years Bess's junior—suggested exactly the same thing when he painted Factum I and Factum II, a pair of canvases that exactly duplicated each others drips and splashes. Rauschenberg went on to become the art star of the sixties by substituting inner tubes and mattresses for meaning-laden brushstrokes and tragic and timeless fields of color. In the summer of 1980 Barbara Haskell, a curator at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art, saw one small Bess canvas at Betty Parson's gallery, was immediately drawn to it, and asked to see more. The result of that chance encounter was a one-man exhibition at the Whitney last fall and an unusually high level of enthusiasm from other artists impressed by the quality, painful sincerity, and originality of Bess's work. The fashions of art, which Bess so despised, now favor him. The aesthetic theories of the fifties and sixties, which were postulated and refined just as obsessively as Bess's psychological theories, have now given way to personal imagery, whether abstract or representational, that is direct to the point of crudeness. Messages, the more idiosyncratic the better, have taken precedence over formalist dogma. "My painting is tomorrow's painting," Bess wrote in 1962 with haunting accuracy. "Watch and see." It is hardly a foregone conclusion that Bess will achieve in death the immortality he searched for in life; that would be an ending that even he didn't hypothesize. But he has already earned a solid footnote in an art history. Right now Roy Fridge wants to complete a film on Bess, and there are plans for scholarly articles and a book. His story is certainly the stuff that creates cult figures, and as it is told his reputation will undoubtedly flourish. More important, although he may never have known it, his art and life achieved the most basic thing that any art or life can aspire to: they touched the people around him. When the Forrest Bess exhibition opened at the Whitney last fall, the show's organizers decided to forgo the usual public reception and hold a small luncheon for the curators, lenders of paintings, and friends of Bess. There were only fifteen or twenty people seated around a big oval table, and when the meal was finished the people who had known him began to reminisce. Meyer Schapiro gave a long, eloquent memorial, and then one story led to another. "It was one of the most moving, touching experiences I ever had," said Rosalie Berkowitz, Bess's old friend from San Antonio and Woodstock. "You actually felt that Forrest was present in that room."

|

||||||||

Forrest Clemenger Bess was born on October 5, 1911, in Bay City, a petrochemical and farming community of 18,000 people sixty miles southwest of Houston, the first child of Arnold "Butch" Bess and his wife, Minta Lee. Butch Bess was an oil driller working the fields at Clemville, a town a few miles from Bay City named after F. J. Clemenger, a Pennsylvania geologist who worked with Butch, discovered the field, and also gave Forrest his middle name. Forrest spent his early years in Clemville and started school in Bay City. A year later, however, his father began to travel from boom town to boom town, and he took his family with him while he wildcatted. It was a robust life far a boy, and Forrest absorbed indelible memories of muddy fields, tents, rain barrels for drinking water, the taste of biscuits sopped in syrup and salt pork grease, the smell of coon and possum hides stretched on boards and drying around the stove.

Forrest Clemenger Bess was born on October 5, 1911, in Bay City, a petrochemical and farming community of 18,000 people sixty miles southwest of Houston, the first child of Arnold "Butch" Bess and his wife, Minta Lee. Butch Bess was an oil driller working the fields at Clemville, a town a few miles from Bay City named after F. J. Clemenger, a Pennsylvania geologist who worked with Butch, discovered the field, and also gave Forrest his middle name. Forrest spent his early years in Clemville and started school in Bay City. A year later, however, his father began to travel from boom town to boom town, and he took his family with him while he wildcatted. It was a robust life far a boy, and Forrest absorbed indelible memories of muddy fields, tents, rain barrels for drinking water, the taste of biscuits sopped in syrup and salt pork grease, the smell of coon and possum hides stretched on boards and drying around the stove.